the double-assignment pattern in jQuery's source code

#javascriptA pattern I discovered in jQuery's source code

You probably never heard of this pattern because I made the name up.

A few years ago, when I just started learning to program, I was looking at the source code of jQuery since it is the most mature JavaScript library out there - until this date, the frontend of amazon.com is still powered by jQuery 1.6.4, and I wanted to learn from the best.

In its source code, I distinctively remember there were code written like this (I omitted a lot of code for simplicity. You can check out its source code if you are interested):

var elemData = someInitialValue

...

elemData.events = elemData = function(){};

...

elemData.events = {};

Back then I couldn't understand why elemData.events got assigned twice. Isn't that a waste of an effort since the last assignment would override the first one anyway? I couldn't know if it was a mistake that jQuery maintainers made or not.

Turns out it is not a mistake. It has something with:

- assignment as an expression

- operator precedence

I will explain how this works in this post. That said, I think this is an obscure corner of the JavaScript language. Although it looks concise or clever, you don't usually need to write code like this.

An assignment is also an expression#

We use assignments to set values to variables every day, but we might not know that besides being statements, assignments are also expressions. The value such an expression evaluates to is the value of the right-hand-side (RHS) of the assignment.

That means we can write code like:

let x

if(x = 1) { // 1 is truthy

console.log(1) // 1

}

And the assignment operator = is right-associative:

let a, b

a = b = 2 // the same as a = ( b = 2)

console.log(a) // 2

console.log(b) // 2

Operator precedence#

Go back to that perplexing jQuery code - elemData.events = elemData = function(){}; - it contains two kinds of operators: two assignment operators and a member access operator as in elemData.events.

When we have different types of operators mixed, operator precedence determines which type of operators take precedence.

According to the precedence table, the member access operator is 18, whereas the assignment operator is only 2. That means the member access operator has higher precedence than the assignment operator. This matches our intuition - during assignments like obj.prop = 1, the first expression that evaluates is obj.prop, resolving to a reference to the prop property and then comes the assignment, not the other way around.

Old elemData vs. new elemData#

Putting these together, let's revisit the mysterious jQuery code snippet:

var elemData = someInitialValue // 1

// ...

elemData.events = elemData = function(){}; // 2

// ...

elemData.events = {}; // 3

Line 1 is pretty straightforward.

There is a lot going on for line 2 - the first elemData and the second elemData are pointing to different values.

Here is a breakdown for line 2:

- First, (the old)

elemDatapointing toinitialValue, and (the old)elemData.eventsproperty pointing to the value of the assignment expressionelemData = function(){} - Second, (the new)

elemDatagets rebound tofunction (){}

For line 3:

- (the new)

elemData.eventsproperty points to{}

Here is a diagram that illustrates what happened conceptually:

This reminds me of the for in loop: when we change the binding of the object (i.e., reassigning a new value to the variable) halfway through the loop, the properties being enumerated will not suddenly change:

let obj = {a: 1, b: 2, c: 3}

let obj2 = {d: 1, e: 2, f: 3}

for(const prop in obj ) {

console.log(prop) // a, b, c

obj = obj2

}

console.log(obj) // { d: 1, e: 2, f: 3 }

Applications#

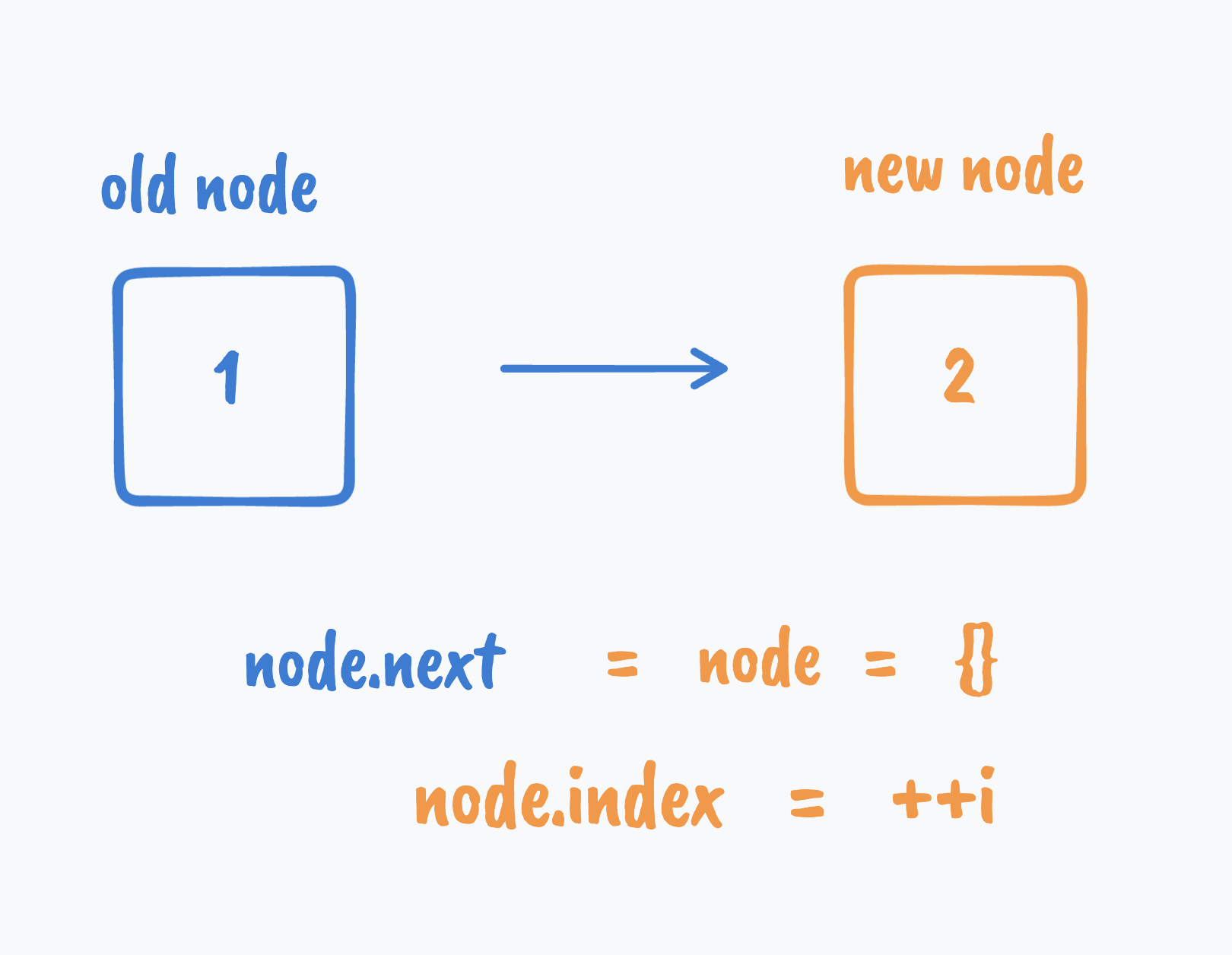

I don't recall seeing code written like this outside of jQuery's source code but I guess you can write a linked list using this pattern:

let i = 0, root = { index: i }, node = root

while (i < 10) {

node.next = node = {} // `node` in `node.next` is the old `node`

node.index = ++i // `node` in `node.index` is the new `node`

}

node = root

do {

console.log(node.index) // 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

} while ((node = node.next))

Here is a diagram that illustrates what happened conceptually: