JSON and the stringification oddities in JavaScript

#javascriptSee discussions on reddit

This post has been translated into Chinese

JSON is one of the things that looked deceptively simple when I first started learning web development. JSON strings looks just like a textual, minimal subset of a JavaScript object. The simplicity makes it (probably) the most popular configuration language.

When I was early in my career, I never took the time to properly study this data format. I just used JSON.stringify and JSON.parse until unexpected errors popped up.

In this blog post, I like to:

- summarize the quirks that I have come across when working with JSON (more specifically the

JSON.stringifyAPI) in JavaScript - consolidate my understanding by implementing a simplified version of

JSON.stringifyfrom scratch

What is JSON#

JSON is a data format invented by Douglas Crockford. You probably already know about this, but what’s interesting is that, as Crockford wrote in his book How JavaScript Works, he admitted that, “The worse thing about JSON is the name.” JSON stands for JavaScript Object Notation, and the problem with this name is that it misleads people to think it only works with JavaScript when in fact it was intended to allow programs written in different languages to communicate effectively.

On a similar note, Crockford also confessed that the two built-in APIs JavaScript provides to work with JSON – JSON.parse and JSON.stringify – were poorly named as well; they should have been called JSON.decode and JSON.encode respectively, because JSON.parse takes a JSON text and decodes it into JavaScript values and JSON.stringify takes a JavaScript value and encodes it into a JSON text/string.

Enough with the naming, let’s take a look at what data types JSON supports, and what happens when a JSON-incompatible value gets stringified by JSON.stringify.

what data types does JSON support#

JSON has an official website where you can look up all the data types it supports, but to be honest the graphs on that page are kind of hard to understand, at least for me, so I prefer the following type annotation:

type Json = null | boolean | number | string | Json[] | { [key: string]: Json };

For any there data type that are not part of the Json union type above, such as undefined, Symbol, BigInt and other built-in objects such as Function, Map, Set, Regex, they are not supported by JSON. Comments are not supported either.

The next logical question is, in the context of JavaScript, what does it mean exactly when we say a data type is not supported by JSON?

Surprising and inconsistent behaviour of JSON.stringify#

In JavaScript, the way to convert a value to a JSON string is via JSON.stringify.

For values of the types that are supported by JSON, they are converted into strings as expected:

JSON.stringify(1); // '1'

JSON.stringify(null); // 'null'

JSON.stringify('foo'); // '"foo"'

JSON.stringify({ foo: 'bar' }); // '{"foo":"bar"}'

JSON.stringify(['foo', 'bar']); // '["foo","bar"]'

But things become messy when there are unsupported types involved during the stringification/encoding process.

When passed directly with unsupported type undefined, Symbol, and Function, JSON.stringify outputs undefined (not the string undefined):

JSON.stringify(undefined); // undefined

JSON.stringify(Symbol('foo')); // undefined

JSON.stringify(() => {}); // undefined

For other built-in object types (except for Function and Date) such as Map, Set, WeakMap, WeakSet, Regex, etc., JSON.stringify will return a string of an empty object literal, i.e. {}:

JSON.stringify(/foo/); // '{}'

JSON.stringify(new Map()); // '{}'

JSON.stringify(new Set()); //'{}'

More inconsistent behaviours occur when the values to be serialized are in an array or in an object.

For unsupported types that result in undefined i.e. undefined, Symbol, Function, when they are found in an array, it gets converted to the string ‘null’, while when found in an object, the entire property gets omitted from the output:

JSON.stringify([undefined]); // '[null]'

JSON.stringify({ foo: undefined }); // '{}'

JSON.stringify([Symbol()]); // '[null]'

JSON.stringify({ foo: Symbol() }); // '{}'

JSON.stringify([() => {}]); // '[null]'

JSON.stringify({ foo: () => {} }); // '{}'

On the other hand, for other built-in object types such as Error, Map, Set, Regex that exist in an array or an object, after the conversion done by JSON.stringify , they all become strings of an empty object literal, i.e. {}:

JSON.stringify([/foo/]); // '[{}]'

JSON.stringify({ foo: /foo/ }); // '{"foo":{}}'

JSON.stringify([new Set()]); // '[{}]'

JSON.stringify({ foo: new Set() }); // '{"foo":{}}'

JSON.stringify([new Map()]); // '[{}]'

JSON.stringify({ foo: new Map() }); // '{"foo":{}}'

Here are a few more exceptions#

-

Since string inputs will be wrapped in double quotes ", (e.g.

JSON.stringify('3') === '"3"'), in order to avoid ambiguity,JSON.stringifywill escape the ones present in the original input using backslashes, such asJSON.stringify('"3"') === '"\\"3\\""'. -

For the recently added new type

BigInt,JSON.stringifythrows aTypeError. The other case whereJSON.stringifythrows an error is when a cyclic object is passed. For the most part,JSON.stringifyis pretty forgiving - it wouldn't make your program crash just because you violate the rules of JSON (unless it isBigIntor cyclic objects).const foo = {}; foo.a = foo; JSON.stringify(foo); // ❌ Uncaught TypeError: Converting circular structure to JSON JSON.stringify(BigInt(1234567890)); // ❌ Uncaught TypeError: Do not know how to serialize a BigInt -

Despite being of the

numbertype,NaNandInfinityget converted intonullbyJSON.stringify. The rational behind the design decision is, as Crockford wrote in his book How JavaScript Works, the presence ofNaNandInfinityindicates an error. He excluded them by making themnullas "we shouldn't put bad data on the wire".JSON.stringify(NaN); // 'null' JSON.stringify(Infinity); // 'null' -

Dateobjects get encoded into ISO strings byJSON.stringifybecause ofDate.prototype.toJSON.JSON.stringify(new Date()); // '"2022-05-19T18:19:54.842Z"' -

JSON.stringifyonly processes enumerable, nonsymbol-keyed object properties. Symbol-keyed non-enumerable properties are ignored:const foo = {}; foo[Symbol('p1')] = 'bar'; Object.defineProperty(foo, 'p2', { value: 'baz', enumerable: false }); JSON.stringify(foo); // '{}'

By the way, hope you can see why it is mostly a bad idea to use JSON.parse and JSON.stringify to deep clone an object.

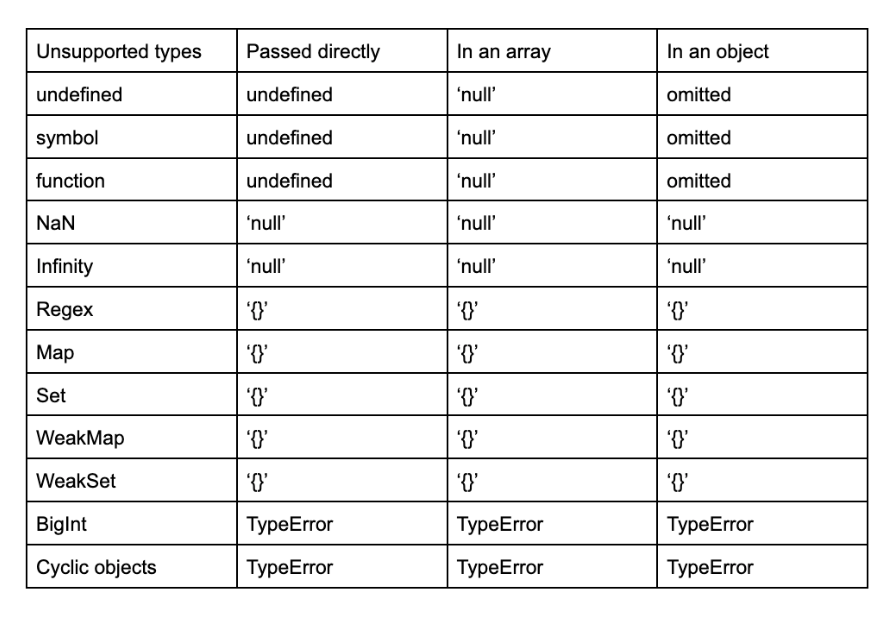

A cheatsheet#

I know this is a lot to remember so I put together a cheatsheet for you to refer to.

Customize the encoding#

What we have discussed so far is the default behaviour of how JavaScript encodes values into JSON strings via JSON.stringify. There are two ways you can take control over the conversion:

-

Adding a

toJSONmethod to the object you passed toJSON.stringify. This is why passingDateobjects toJSON.stringifydoesn't lead to an empty object literal because aDateobject inherits atoJSONmethod from its prototype.const foo = { toJSON: () => 'bar' }; JSON.stringify(foo); // 'bar' -

JSON.stringifytakes an optional parameter called replacer, which can be either a function or an array, to alter the default behavior of the stringification process.

ss

Implement a simplified JSON.stringify from scratch#

I heard people ask this in a technical interview. Here is my attempt.

I skipped the optional

replacerandspaceparameters for brevity.

const isCyclic = (input) => {

const seen = new Set();

const dfsHelper = (obj) => {

if (typeof obj !== 'object' || obj === null) return false;

seen.add(obj);

return Object.values(obj).some((value) => seen.has(value) || dfsHelper(value));

};

return dfsHelper(input);

};

function jsonStringify(data) {

const quotes = '"';

const QUOTE_ESCAPE = /"/g;

if (isCyclic(data)) {

throw new TypeError('Converting circular structure to JSON');

}

if (typeof data === 'bigint') {

throw new TypeError('Do not know how to serialize a BigInt');

}

if (data === null) {

// Handle null first because the type of null is 'object'.

return 'null';

}

const type = typeof data;

if (type === 'number') {

if (Number.isNaN(data) || !Number.isFinite(data)) {

// For NaN and Infinity we return 'null'.

return 'null';

}

return String(data);

}

if (type === 'boolean') return String(data);

if (type === 'function' || type === 'undefined' || type === 'symbol') {

return undefined; // Not the string 'undefined'.

}

if (type === 'string') {

return quotes + data.replace(QUOTE_ESCAPE, '\\"') + quotes;

}

// at this point `data` is either an array, an plaid object, or other unsupported object types such as `Map` and `Set`

if (typeof data.toJSON === 'function') {

// If data has user-provided `toJSON` method, we use that instead.

return jsonStringify(data.toJSON());

}

if (data instanceof Array) {

// Array.prototype.toString will be invoked implicitly during string concatenation.

return '[' + data.map((item) => jsonStringify(item)) + ']';

}

// data is a plain object.

const entries = Object.entries(data)

.map(([key, value]) => {

const shouldIgnoreEntry =

typeof key === 'symbol' ||

value === undefined ||

typeof value === 'function' ||

typeof value === 'symbol';

if (shouldIgnoreEntry) {

return;

}

return quotes + key + quotes + ':' + jsonStringify(value);

})

.filter((value) => value !== undefined);

// Again, Object.prototype.toString will be invoked implicitly during string concatenation

return '{' + entries + '}';

}

A faster JSON.stringify#

It's quite obvious that the implementation of JSON.stringify involves frequent runtime type checks due to the dynamic typing nature of the JavaScript language. One way we can make our own implementation of JSON.stringify faster is to have the user provide a schema of the object so we know the object structure before serialization. This can save us a ton of work. In fact, many JSON.stringify-alternative libraries are implemented this way to make serialization faster. One example would be fast-json-stringify

Further Reading#

- the stringify spec

- There are some criticisms of JSON as a configuration language. Check out Why JSON Isn't a Good Configuration Language if you are interested in the alternatives.