When does React render your component?

#reactWhen and why does React render my component exactly?

This post has been translated into Korean

This post is my version of Mark Erikson's essay A (Mostly) Complete Guide to React Rendering Behavior where I try to answer one of the most commonly asked questions in this React community – "when or why does React render my component?" – with a tiny amount of React source code walkthrough.

Normally I am not a big fan of drilling down to the implementation details and you certainly don't need to know that in order to be productive in React. However, when it comes to understanding the rendering behaviour and rules for bailing out of re-renders, the React docs haven’t provided a thorough enough explanation to satisfy me. Therefore to adequately answer those questions, I had to peek into the source code. That being said, this is not going to be a post about hard-core source code walkthrough. If you are interested in that, here is a great series made by JSer that you should check out.

Tl;dr#

- React (re)renders your component when:

- there is a state update scheduled by your component

- including updates scheduled by custom hooks your component consumes

- the parent component got rendered and your component doesn’t meet the criteria for bailing out on re-rendering, where all these four conditions have to be satisfied at the same time:

- Your component has been rendered before i.e. it already mounted

- No

props(referentially) changed - No any context value consumed by your component changed

- Your component itself didn’t schedule an update

- there is a state update scheduled by your component

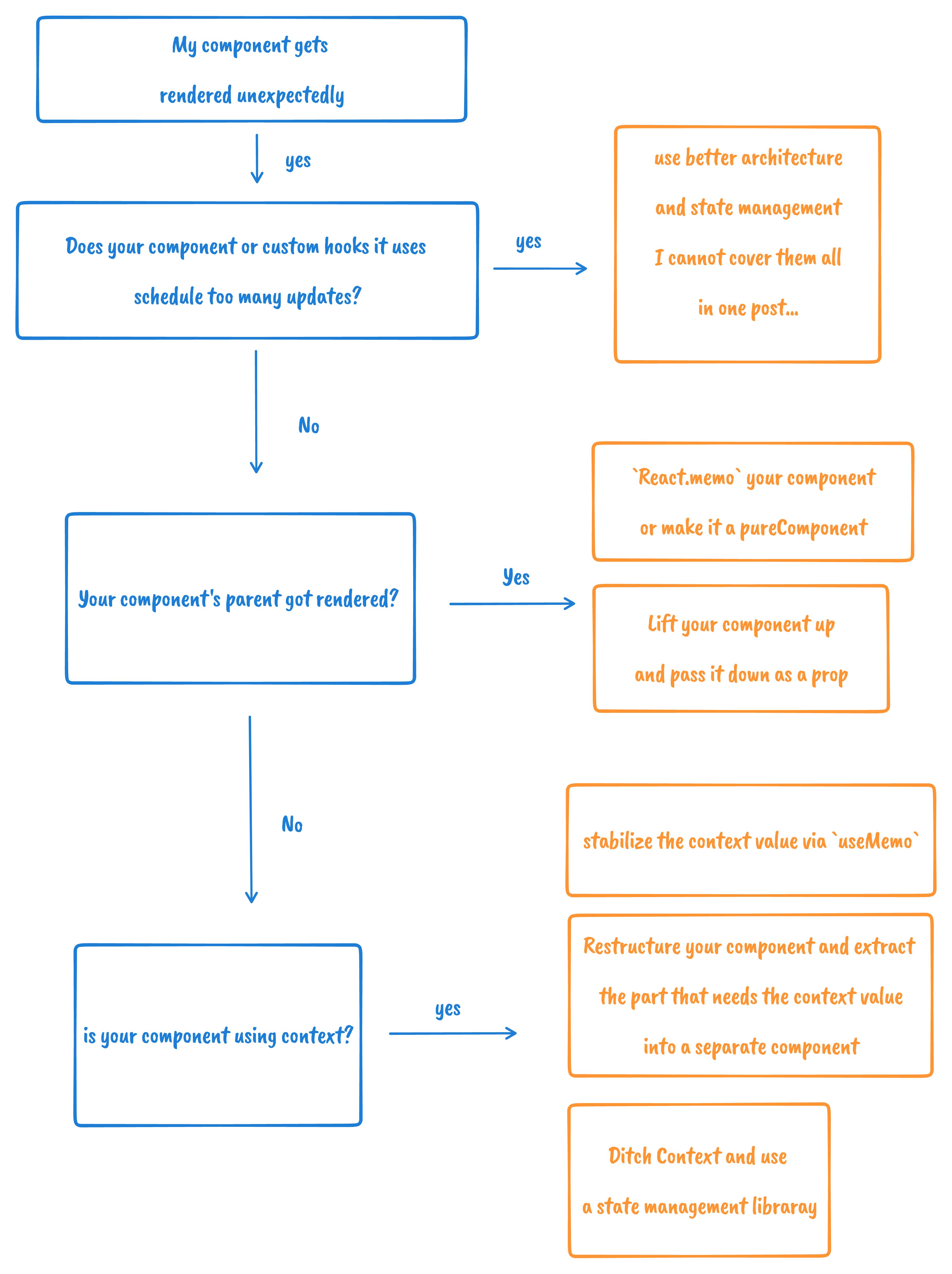

- You probably shouldn’t need to worry about seemingly unnecessary re-renders until it becomes a performance issue. Check out the flow chart I made for solutions you can adopt when a performance issue occurs.

Disclaimer: I haven't used React's concurrent mode so some parts of this post might not be applicable in concurrent React.

What does the word “render” mean?#

I don’t know if you have noticed this – I kept saying “React renders your component”, as opposed to “your component renders”. People use them interchangeably. It is largely an arbitrary decision. However, call me pedantic but I do want to use the former exclusively in this post because it describes how React works more accurately. Your components – functions augmented by React with the ability to schedule an update on the UI – are called by React, not the other way around, regardless of whether that render was a result of your component proactively changing its own state or some other changes.

As one of its core design principles, React has full control over scheduling and updating the UI. This means a few things to us:

- One state update made by our component doesn’t necessarily translate into one render (one invocation of your component by React) because:

- React might not think there are any meaningful changes to your component’s state (determined by

object.is) - React tries to batch state updates into one render pass.

- However, React cannot batch state updates in promises, because React has no control over when they are resolved, same thing with native event handlers,

setTimeout,setInterval, andrequestAnimationFrame, all of which are running much later in a totally separate event loop call stack

- However, React cannot batch state updates in promises, because React has no control over when they are resolved, same thing with native event handlers,

- React might split the work in chunks across different render passes (a concurrent React feature)

- React might not think there are any meaningful changes to your component’s state (determined by

- One render to your component doesn’t necessarily translate into a visual update on the UI because React could decide to render your component (i.e. call your function) for a variety of reasons.

In React 17, some state updates cannot be auto-batched...

In React 17, some state updates cannot be batched, such as updates in promises, because React has no control over when they are resolved, same thing with native event handlers, setTimeout, setInterval, and requestAnimationFrame, all of which are running much later in a totally separate event loop call stack

In React 18, all state updates can be auto-batched.

However, having React in control of rendering doesn’t mean you shouldn’t care about when or why it decides to render your component. We can’t rely on React to have us back. Understanding the underlying mechanism React uses to render your components comes in handy when we face performance issues.

Let's also define what "update" means in different contexts...

Alongside the word “render”, the word “update” is going to be used a lot. It means different things in different contexts.

When used in “your component schedules an update”, it means the component wants to change its own state and ask React to reflect that change on the UI. Here the update is the reason that React would render (call) your component. Note that at the end whether React decides to render your component, how many times React decides to render your component and in how long a delay it decides to render depends on a variety of factors.

When used in “React makes an update to the UI”, it means it either React mutates an existing DOM node or creates a new DON node to match its internal representation of the DOM tree. Here the update is the result of rendering your components

So when does React render your component exactly?#

There are two types of rendering that can happen to your component:

- proactive rendering:

- Your component (or the custom hooks it consumes) proactively schedules updates to change its own state.

- You call

ReactDOM.renderdirectly.

- passive rendering: The parent component(s) schedule state updates and your component doesn’t meet the bail-out criteria.

Proactive rendering#

"proactive rendering" is a made-up word by me. By "proactive", I mean the component itself (or the custom hooks it uses) proactively makes changes to its own state to schedule updates via:

- Component.prototype.setState (i.e.

this.setState) if it is a class components. - dispatchAction exposed by Hooks if it is a function components:

- Both the

dispatchfunction from theuseReducerHook and the state updater function from theuseStateHook usedispatchActionunderlying.

- Both the

Another way to proactively schedule an update is to call ReactDOM.render directly. Here is an example in React official docs:

function tick() {

const element = (

<div>

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

<h2>It is {new Date().toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2>

</div>

);

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById('root'));

}

setInterval(tick, 1000);

More implementation details for the rendering phase...

Regardless of which exact function you used to schedule the update, all the them use the scheduleUpdateOnFiber in the reconciler, which–you can probably tell by its self-explanatory name–schedules updates on Fiber.

But what is a Fiber? Fiber was introduced in React 16. It is the new reconciliation algorithm and also a new data structure to present a unit of work internal to React. A fiber node is created from a ReactElement by the reconciler. Normally every ReactElement has a corresponding fiber node but there are some exceptions. For example, a Fragment type of ReactElement doesn’t have a corresponding fiber node.

One major distinction between a fiber node and a ReactElement is that a ReactElement is immutable, getting re-created all the time while a fiber node is mutable and can be reused. When React bails out on rendering a component, it reuses its current corresponding fiber node in the fiber tree it constructs as opposed to create a new one.

This is not a post about React internals. You can check out this article if you want to learn more about fiber nodes and the whole reconciliation process.

Passive rendering#

Passive rendering happens to your component because React rendered some parent component(s) and your component does not meet the bail-out criteria.

function Parent() {

return (

<div>

<Child />

</div>

);

}

In the example above, if Parent gets rendered by React, Child also gets rendered even though its props have no meaningful changes other than that its reference/identity changed. (More on this later)

During the render phase, React recursively traverses down the component tree to render your components. As a result, if Child has other children components, they would get rendered too (again, if they don’t meet the bail-out criteria)

function Child() {

return <GrandChild /> // if `Child` gets rendered, `GrandChild` is rendered too

}

However, if one of these components meets the bail-out criteria, React will not render that component.

The next logical question is, what are the bail-out criteria?

To answer that, let’s us take a look at two examples.

Not every child component is created equal#

Let’s first a look at an example:

default function App() {

return (

<Parent lastChild={<ChildC />}>

<ChildB />

</Parent>

);

}

function Parent({ children, lastChild }) {

return (

<div className="parent">

<ChildA />

{children}

{lastChild}

</div>

);

}

function ChildA() {

return <div className="childA"></div>;

}

function ChildB() {

return <div className="childB"></div>;

}

function ChildC() {

return <div className="childC"></div>;

}

If Parent schedules an update, which component(s) will get re-rendered?

Unsurprisingly, Parent itself will get re-rendered by React since it is the component that schedules the update. But will all the children ChildA, ChildB and ChildC get re-rendered as well?

To answer that question, I prepared a Hook called useForceRender to schedule re-renders at some interval via setInterval

function useForceRender(interval) {

const render = useReducer(() => ({}))[1];

useEffect(() => {

const id = setInterval(render, interval);

return () => clearInterval(id);

}, [interval]);

}

I use it inside Parent and see which child gets re-rendered:

function Parent({ children, lastChild }) {

useForceRender(2000);

console.log("Parent is rendered");

return (

<div className="parent">

<ChildA />

{children}

{lastChild}

</div>

);

}

ChildA got re-rendered, which shouldn’t be surprising to us since we know that its parent scheduled the updates and got re-rendered as a result.

However, unlike ChildA, ChildB and ChildC didn’t get re-rendered. Because ChildB and ChildC met the bail-out criteria, so React skipped rendering them.

This might not be news to you. Kent C. Dodds, Dan Abramov and Mark all have written about this optimization technique in their blog posts.

Context consumers get rendered whenever the provider get rendered#

Passive rendering can also happen when your component is a context consumer.

Let’s tweak our previous example to make Parent a context provider and ChildC a context consumer.

const Context = createContext();

export default function App() {

return (

<Parent lastChild={<ChildC />}>

<ChildB />

</Parent>

);

}

function Parent({ children, lastChild }) {

useForceRender(2000);

const contextValue = {};

console.log("Parent is rendered");

return (

<div className="parent">

<Context.Provider value={contextValue}>

<ChildA />

{children}

{lastChild}

</Context.Provider>

</div>

);

}

function ChildA() {

console.log("ChildA is rendered");

return <div className="childA"></div>;

}

function ChildB() {

console.log("ChildB is rendered");

return <div className="childB"></div>;

}

function ChildC() {

console.log("ChildC is rendered");

const value = useContext(Context)

return <div className="childC"></div>;

}

Here is the result:

Every time Parent get rendered (called) by React, it creates a new contextValue, which is different referentially compared to the previous contextValue. As a result, the context consumer ChildC gets a different context value, and React go ahead and re-render ChildC to reflect that change.

Note that if contextVlaue were a primitive value, e.g. number or string, then its equality wouldn’t change between re-renders, and as a result, ChildC wouldn't get re-rendered.

Note that bail-out is on individual-component level

If one of these components meets the bail-out criteria, React will not render that component. However, React would still proceed to check if there are any updates needed for the children of the bailed-out component though. In the example below, while ChildA and ChildB get bailed out, their descendent – ChildC – still gets re-rendered whenever Parent gets re-rendered.

function useForceRender(interval) {

const render = useReducer(() => ({}))[1]

useEffect(() => {

const id = setInterval(render, interval)

return () => clearInterval(id)

}, [interval])

}

function App() {

return (

<Parent>

<ChildA />

</Parent>

)

}

function Parent({ children }) {

useForceRender(1000)

const contextValue = {}

console.log('Parent is rendered')

return (

<div className="parent">

<Context.Provider value={contextValue}>{children}</Context.Provider>

</div>

)

}

function ChildA() {

console.log('ChildA is rendered')

return (

<div className="childA">

<ChildB />

</div>

)

}

function ChildB() {

console.log('ChildB is rendered')

return (

<div className="childB">

<ChildC />

</div>

)

}

function ChildC() {

console.log('ChildC is rendered')

const value = useContext(Context)

return <div className="childC"></div>

}

Bail-out criteria#

We have seen enough examples, so let’s talk about what the bail-out criteria really are.

To get the ground truth, we have to dig into the source. But where do we even start?

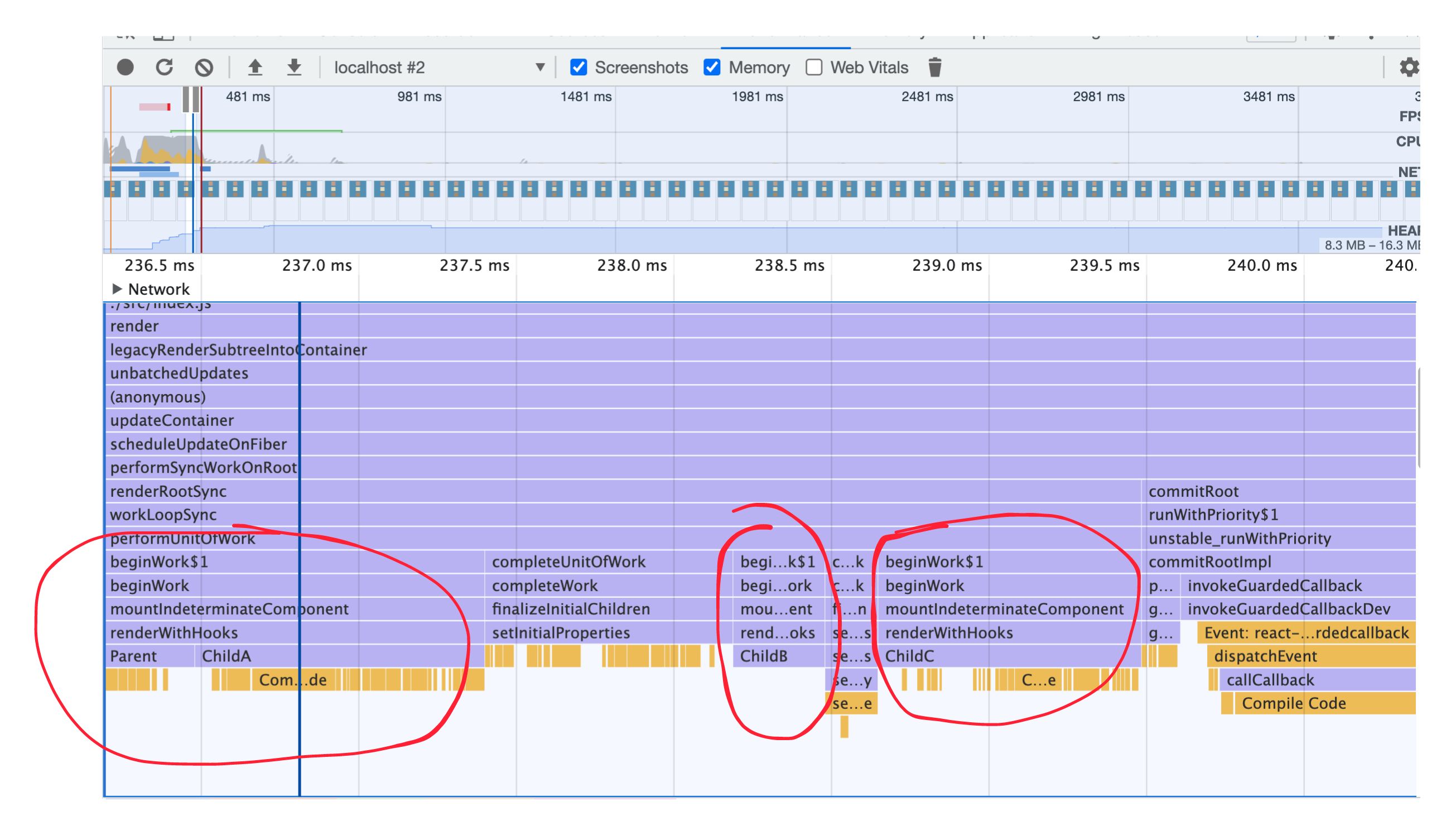

We can profile the app in the performance tab to see the call stack during the runtime.

The above screenshot is a snapshot of the call stack when our App first mounted.

Our app was mounted by ReactDOM.render, resulting an update scheduled via scheduleUpdateOnFiber. This is the entry point for React to update fiber nodes, regardless if React renders the component for the first time or not.

There are too many details involved but a pattern we can recognize is that for every component React renders, it needs to call beginWork. It seems like the place where the secrete about the bail-out behaviour would lie.

Let’s take a look at its source code:

It is a long function. It accepts three arguments: current, workInProgress and renderLanes. Current is a pointer to the existing fiber node, workInProgress is a pointer to the new fiber node being constructed to reflect the update. Why are there two fiber nodes involved for each update? This is called double buffering, an optimization technique to improve perceived performance.

Although there is a lot going on in this function (as well as in this file), it is not hard to find where exactly React enters the bail-out logic:

// ...omitted for brevity

// No pending updates or context. Bail out now.

didReceiveUpdate = false;

return attemptEarlyBailoutIfNoScheduledUpdate(

current,

workInProgress,

renderLanes,

);

In order for us to reach this line, these conditions have to be satisfied:

current !== nulloldProps === newPropshasLegacyContextChanged() === falsehasScheduledUpdateOrContext === false

This roughly translates to:

- Your component has been rendered before i.e. it already mounted

- No

propschanged - No any context value consumed by your component changed

- Your component itself didn’t schedule an update

Rule 1 and rule 4 are easy to understand.

Let’s focus on Rule 2 and Rule 3.

How to not change props#

A component’s props is a property of its corresponding ReactElement, created by React.createElement. Because ReactElements are immutable, every time React renders (calls) your component, React.createElement is called to produce a new ReactElement. As a result, your component's props is created from scratch for every re-render.

Look back on our first example:

function Parent() {

return (

<div>

<Child />

</div>

);

}

The <Child /> returned from Parent gets compiled to React.createElement(Child, null) by Babel, and that creates a ReactElement of this shape {type: Child, props: {}}

Since props is an JavaScript object, so its reference changes every time it gets re-created. By default, React uses === to compare the previous props and the current props. As a result, the props are considered different between re-renders. That’s why even though Child receives nothing from Parent as part of its props, it still gets re-rendered whenever Parent gets re-rendered – React.createElement is called for Child and that creates a new props object.

However, if we can lift Child up and pass it down via Parent’s props:

function App() {

return <Parent><Child /></Parent>

}

function Parent({children}) {

return (

<div>

{children}

</div>

);

}

Then whenever Parent gets rendered by React, there is no React.createElement function call for Child. As a result, no new props created for Child, and that makes it meet all all four bail-out rules I mentioned above.

This is why in this example, only ChildA gets re-rendered whenever Parent schedules an update:

function Parent({ children, lastChild }) {

return (

<div className="parent">

<ChildA /> // only ChildA gets re-rendered

{children} // bailed out

{lastChild} // bailed out

</div>

);

}

How to change the rule React uses to detect props changes#

I mentioned that, by default, React uses === to compare the previous props and the current props.

Luckily, React provides an alternative way to detect props change if we make our component a PureComponent or wrap it in React.memo. In those cases, instead of using === to check if the reference changed, React would shallow compare every property in the props, conceptually similar to Object.keys(prevProps).some(key => prevProps[key] !== nextProps[key]).

However such optimization should not be abused and there are reasons why React didn’t make it the default rendering behaviour. Dan Abramov has repeatedly pointed out that we should not ignore the costs of comparing

propsand a lot of times there are better alternatives.

How to not change context values#

If your component is a consumer of some context value, then when the provider gets re-rendered and the context value is changed (even only referentially), your component gets re-rendered too.

This is why in this example, the context consumer ChildC gets re-rendered whenever Parent gets re-rendered:

const Context = createContext();

export default function App() {

return (

<Parent lastChild={<ChildC />}>

<ChildB />

</Parent>

);

}

function Parent({ children, lastChild }) {

useForceRender(2000);

const contextValue = {};

console.log("Parent is rendered");

return (

<div className="parent">

<Context.Provider value={contextValue}>

<ChildA />

{children}

{lastChild}

</Context.Provider>

</div>

);

}

function ChildC() {

console.log("ChildC is rendered");

const value = useContext(Context)

return <div className="childC"></div>;

}

Note this is not bad per se. The compound component pattern relies on this exact rendering behaviour of context consumers. However it can become a performance issue when a provider has too many consumers or consumers that are too expensive to get re-rendered unnecessarily.

In which case, the easiest fix is to wrap your non-primitive context values into useMemo so they stay referentially the same between re-renders of the provider component:

function Parent({ children, lastChild }) {

const contextValue = {};

const memoizedCxtValue = useMemo(contextValue)

return (

<div className="parent">

<Context.Provider value={memoizedCxtValue}>

<ChildA />

{children}

{lastChild}

</Context.Provider>

</div>

);

}

There is one exception where you don't want to use useMemo to wrap context values

You can wrap context values inside useMemo as a performance optimization technique if the consumer subtree can be huge.

However there is one exception to this – if the context provider component is at the top of the component tree, then there is no point in memoizing the context value – as no passive rendering can happen to it. For example:

const ContextA = createContext(null);

const Parent = () => {

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, initialState);

const value = useMemo(() => [state, dispatch], [state]);

return (

<ContextA.Provider value={value}>

<Child1 />

</ContextA.Provider>

);

};

If Parent is at the top of the component tree, i.e. it doesn’t have any other parent components, then the only reason React would re-render it is dispatch is called, in which case the memoization we applied via useMemo would be busted anyway and as a result the subtree is re-rendered. So we are better off passing down the value directly, as in:

const ContextA = createContext(null);

const Parent = () => {

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducerA, initialStateA);

return (

<ContextA.Provider value={[state, dispatch]}>

<Child1 />

</ContextA.Provider>

);

};

There are many other techniques you can employ to optimize context consumption. My friend Vladimir has a great post on this that you should check out.

It is all based on one implicit premise...#

My confession to you is that the whole bail-out thing is based on the premise that your component is always rendered in the same place in the component tree. The reason I didn’t state that upfront is because normally that is the case. However if you:

- switch between different component types at the same position

- render the same component at the different position

- deliberately change its

key

...then react will destroy the entire subtree and re-build it from scratch. Not only will your component get re-rendered, but also its state will be lost.

Check out the Preserving and Resetting State from new React docs to learn more about this.

What’s the moral?#

Whether you found the bail-out rules complex or not, one simple idea I would like you to walk away with is that – React could re-render your component for a variety of reasons.

It is necessary for React to do so because two of the hardest problems in UI engineering is to avoid inconsistency and staleness in your app’s states.

Therefore, make sure your component is ready for re-renders and be resilient to a lot of them. You can stress-test your component with the hook I made (an idea I stole from Dan Abramov). Furthermore, make your component idempotent so rendering your component one time or multiple times shouldn’t cause any differences on the actual UI (except for the performance drop it incurred).

However, when excessive re-rendering causes two other hardest problems in UI engineering – responsiveness and latency, hopefully you already know where to investigate and how to optimize.

The flow chart#

I made a flow chart that might be helpful for you to check for unexpected re-render: